Pioneer

A short discussion on my favorite book about finance, *Pioneering Portfolio Management* by David Swensen

How do you make a giant pile of money last forever?

The late David Swensen, the longtime manager of Yale’s endowment, answers this question in his book, Pioneering Portfolio Management, one of the best books about finance that I’ve read. Swensen does an excellent job demystifying a notoriously abstruse and jargon-filled field to the lay reader. I highly recommend reading it, and will summarize its main takeaways here.

The financial community credits Swensen as one of the inventors of what has become known as the “Yale model,” an investment approach that revolutionized how universities, foundations, pensions, and other large institutions manage their money. And, because big institutional investors represent a huge fraction of the demand for investable assets, Swensen also transformed the sell-side of the financial industry as well (some might say for the worse), shifting the focus from public market equities and bonds to private market PE, venture capital, and hedge funds.

What are the goals of a portfolio manager?

You have a giant pile of money. Congratulations! Now how should you manage it?

The answer to this question depends on what your goals are for your giant pile of money. For most personal investors, you’re thinking about retirement. You put money into your retirement savings so that you can one day stop working, make zero income, and still have the means to play golf and go on cruises. But that eventuality could be a long ways away; as a 30 year old, your money has to sit around for a while before you need it.

This brings us to the fundamental concept of the risk-return tradeoff.1 Consider two assets you could own: a stock at a cryptocurrency-backed AI-enhanced nuclear fusion startup, and a US Treasury bond with an interest rate of 3%. The startup has a highly variable average rate of return—it could solve nuclear fusion and become the most profitable business in the history of industrial capitalism, or it could all be an elaborate scam and lose all of your money. Your returns are bounded somewhere between [-100%, +∞%). The Treasury bond, on the other hand, will return 3% unless the US Government goes under.2 Given that that is unlikely, in expectation, your returns are bounded between (2.9999…%, 3%].

This illustrates the tradeoff. You can have high returns, or you can have consistent returns, but you generally can’t have both.

So, for a personal investor with a stated goal of “have a lot of money when you retire,” the optimal strategy is usually something like: invest in riskier but higher-upside assets (like stocks) in the decades where your retirement is distant. Then, as your retirement date looms, you should gradually shift your portfolio towards lower returning but less volatile assets (like bonds). This is what many consumer retirement products, like the target date funds that Vanguard and Fidelity invest in by default, do in practice.

But now consider you’re the manager of the endowment of Yale University. You now are in charge of a much giant-er pile of money. And instead of needing to save for a distant retirement, you need to use it to fund the consistent operations of a university: pay the salaries of tenured professors, dole out financial aid, build a campus in Abu Dhabi, and so on. There is no “target date” for a university endowment. Indeed, the legal purpose of an endowment is that it lasts forever. So the goal of an endowment manager, in contrast to a personal investor, is something closer to: (1) grow the endowment over time, and (2) supplement the day-to-day operations of the university as much as you can, as consistently as you can, insofar as this does not compromise (1).

The magic of diversification

The problem with this is that generating high, stable returns is hard. Most financial markets are crowded; there is so much information going into the day-to-day fluctuations of the markets that many financial theorists hypothesize that the best model of their fluctuation is a martingale—their movements are random, conditional on their past prices. In such an environment, it’s effectively impossible to generate consistently high returns just by picking stocks on a hunch.

Instead, a hack-ish way to ensure stability in returns on one’s investments is the Law of Large Numbers: You can just buy all the stocks. As an investment manager, this requires very little work for you—in finance parlance, it’s a passive, as opposed to active investment strategy. And stocks generally go up over time, so this strategy ensures decent returns as well.

But equities are all similar in a critical way: They’re all equities. And, as I’m sure you know, stock markets crash! If you had bought an all-stock portfolio of the S&P 500 in October of 2007, it would have taken you six years to get your money back.

A university can’t go six years without any returns at all. But lucky for you, you don’t need to just buy stocks. You can diversify across asset classes as well. Swensen goes through each asset class in detail, but for the purposes of this post you really only need to know the highlights:

Stocks (or equities): This is a chunk of a publicly-traded company, and gives you a share of a company’s profits in the form of dividends. Of all asset classes, on average equities generally have both the highest returns and the highest risk.

Bonds (or fixed income): This is a structured loan to a company or a government entity. Bonds tend to be more stable because large institutions issue them. Also, bondholders are often first in line to reclaim their value when a company goes into Chapter 11 bankruptcy. This means that bonds tend to have lower (or even fixed) returns over time, concomitant with lower risk.

Real estate: As Tony Soprano famously said: “Buy land, AJ, God ain’t making any more of it.” Swensen conceives of real estate investment as a kind of mix between equities and bonds. Real estate has some equity-like properties in the sense that real estate tends to appreciate in value over time; it also has some bond-like properties in that you can often lease the property out and derive a fixed income stream from it. For these reasons, real estate is often a midpoint between bonds and equities on the risk-return tradeoff scale.

Alternative investments: These assets take a variety of forms, which I’ll summarize below but it’s not really important within the scope of this piece to understand them in-depth:

Private equity: These funds generally raise capital and take on debt in order to take over struggling businesses and turn around their operations. PE firms generally re-sell these businesses after 3-5 years.

Venture capital: As distinct from PE, venture capital funds invest in very early-stage companies, with the expectation that some of them will grow tremendously over long time horizons.

Hedge funds: These funds take on investments with far-shorter time horizons (at maximum a few months), and usually rely on complicated financial engineering and mathematics to quantify risk and engage in arbitrage.

The magic of diversifying across asset classes lies in the fact that all of these investments generate returns in distinct, uncorrelated3 ways. In an ideal world, alternative investments would not all tank at the same time and with the same magnitude that the stock market does. Indeed, hedge funds are referred to as such because their originally conceived purpose was to provide an uncorrelated “hedge” against bad market outcomes.

A core component of the Yale model that Swensen pioneered was the recognition that universities were overexposed to stocks and underexposed to alternative investments like private equity, venture capital, and hedge funds. Prior to Swensen, universities often sought the higher returns associated with stocks, thinking that their long-term outlook would enable to weather the big crashes relative to shorter-term investors. Swensen recognized that universities could still enjoy high returns (and avoid catastrophic losses) by concentrating more of their balance sheet to these more opaque, less liquid investment vehicles.

Activity, passivity, and the illiquidity premium

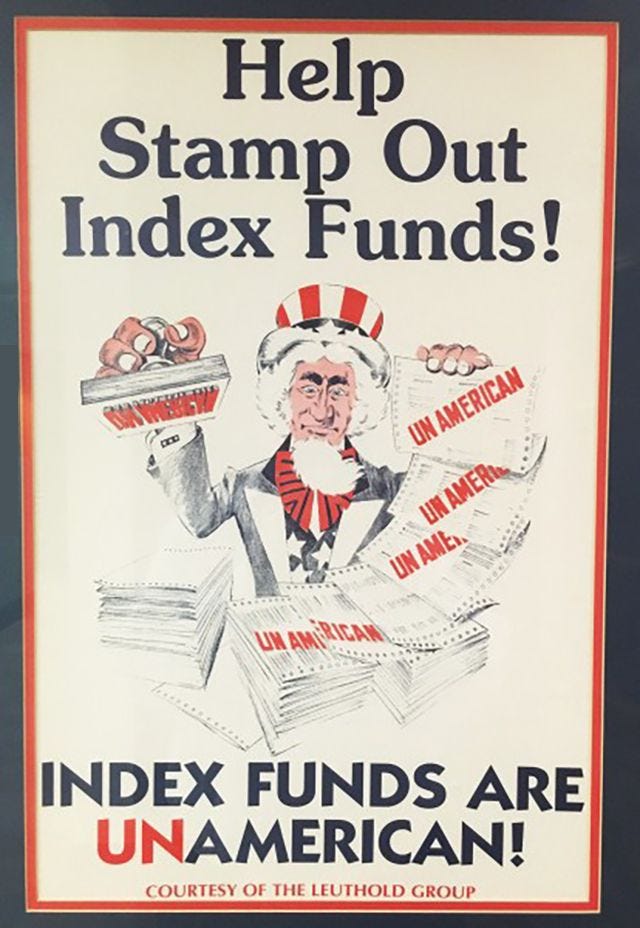

So is portfolio management all just diversification? Should you just buy index funds, and buy into a representative sample of the other asset classes, to smooth out risk and ensure consistent returns as the economy goes up?

If you’re the Nevada state employees’ pension system, the answer is yes. And for personal investors, a well-diversified passive approach between stocks and bonds often makes the most sense, as target date funds attest. But there are a few issues with the fully passive approach4 for a large, well-resourced institution like a university or foundation.

One issue is that average returns are … well, average. If you’re Yale University, you can afford to pay smart, expensive financiers to dedicate their time and intellect to generate better than average returns. After all, if beating the market were impossible, then no one would hire active money managers. But, given how hard it is to pick stocks, how do they do it?

This dovetails with another issue with the fully passive approach, one that Warren Buffet famously observed: On average, alternative investments actually underperform more popular asset classes like stocks and bonds. If an endowment simply invested in a market-representative index of all private equity and hedge funds, they’d achieve worse returns than if they had simply bought all the stocks in the S&P 500. A big reason for this is fees: most PE and hedge funds charge “two and twenty”—a flat 2% fee for the total amount of assets under management regardless of how well the fund actually does, and 20% cut of the profits, if any, that the fund generates.

Early in his book, Swensen points out that the reason that large institutional investors can benefit from active management is related to the reason why they also can benefit from alternative investments: Markets in alternatives are illiquid.

A liquid market is one with a lot of activity and high visibility of prices. Financiers sometimes refer to liquid markets as “deep,” in the sense that they are crowded with buyers and sellers, and the second-by-second prices remain relatively stable.5 The markets for shares in private equity and hedge funds, however, are definitionally illiquid. Investors in alternative assets often sign non-public term sheets, and can’t withdraw their money except on contractually-stipulated timelines. For this reason, one can’t just go onto a brokerage account and see what a share of a hedge fund like Jane Street is worth. And for institutional investors, this illiquidity is useful for two reasons.

First, Swensen argues that markets tend to structurally overvalue liquidity. Interestingly, this aligns with a concept that the economist John Maynard Keynes called the “fear of goods.” Most investors would rather hold liquid investments—assets that they can easily sell on a moment’s notice—rather than take on the risks of a truly illiquid investment. Liquidity affords the investor an escape hatch.6

But for a large institution, you generally have a long enough investment horizon to take longer-term bets. Yale has a large enough endowment that they can afford to lock up a portion of their funds in more illiquid vehicles. Note that this is a distinct property from the ability to bear risk itself. It’s not that Yale is taking on inherently riskier investments—it is taking on investments that require longer duration and have fewer off-ramps along the way.

Second, because alternative investments are illiquid, there are more opportunities for active managers to beat the market. Even a good portfolio manager likely cannot consistently win when picking liquid assets like stocks. After all, every major investment bank employs a full team of analysts whose entire job is to learn everything there is to know about every corner of the public markets. But in illiquid markets, less information is available. This makes it more likely that a good portfolio manager can spot an opportunity for above-market returns at a bargain.

This is not to say that these opportunities are easy to come by. As I noted above, on average, portfolio managers would be better off simply putting their money in stocks than hedge funds and private equity firms. It’s a bit like the old quip about advertising—50% of hedge funds fail, the problem is identifying which 50%. The top performing hedge funds and private equity firms can generate well-above market returns. But the market inefficiencies that these select firms exploit are finite in scale. Great private investment firms like Sequoia Capital and Bridgewater don’t just take anyone off the street on as a limited partner.7 A good portfolio manager can recognize and jump on these high-return opportunities. And, indeed, David Swensen did, setting up Yale as a key beneficiary to the rise of the private capital markets.

In this way, investing in alternatives requires far more discretion on the part of the portfolio manager. It becomes less about convoluted mathematical models, supermassive quantities of data, and transatlantic fiber-optic cables, and more about instinct, judgment, interpersonal relationships, and culture.

In sum

Why does David Swensen matter?

When people think about finance in the 21st century, they generally think about the faces on the frontend of financial markets: larger-than-life hedge fund managers like Ken Griffin, George Soros, and Steve Cohen, PE managers like Steven Schwarzman and Leon Black, venture capitalists like Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen. These are the faces that dot the pages of the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal; in many ways, they’re synonymous with our present stage of what Hyman Minsky called “money manager capitalism.”

But there is another side to money management that does not enjoy the glitzy cache of managing a major private fund: the institutions. By focusing on the titans of high finance, we obscure the people that the titans work for: the pensions, retirement accounts, college savings, and endowments. And indeed, in some ways, these are the really the load-bearing beams of entire financial system. As Ben Bernanke observed looking back on the Great Financial Crisis, the collapse in the housing market alone really wasn’t large enough to put a dent in the overall economy. The problem was that the housing market crash had exposed vulnerabilities in the money markets, which in turn exposes unexpected risks to institutional investors. That is how bad bonds on the balance sheets of some banks translated into the fear that public pensions wouldn’t be able to pay out to retirees.

And, on the surface, the revolution in institutional investing that Swensen kicked off seems coextensive with some of the morbidities in the financial system that the GFC exposed: private, illiquid markets operating outside the confines of the legible scrutiny of regulators and watchdogs. On the power hand, maybe the tremendous power these investors retain can really drive positive social progress, or even save the world. As Keynes and Swensen teach us, illiquidity can be a liberating force, as well as a destructive one.

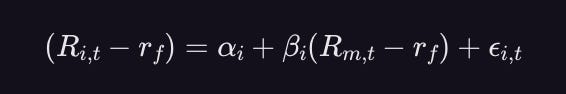

One of the first observers of the relationship was William Sharpe, often credited with the creation of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) and namesake of the Sharpe ratio, a key metric in finance that measures risk-adjusted returns.

Which, after the downgrade in the United States government’s credit rating, is maybe more probable than is ideal?

Within the fancy parlance of Sharpe’s CAPM framework, alternative investments have a “low beta." Sharpe originally formulated the expected returns of a given investment as a linear regression:

In this formulation, “beta” represents the expected return associated with a given factor across the market. An investment with “high alpha” and “low beta” means that most of the investment’s returns derive not from the investments underlying, market-wide factors, but instead from the idiosyncrasies of the investment itself, such as the hedge fund manager being a genius or the PE manager being particularly good at exploiting the bankruptcy code.

There’s also some more philosophical issues related to price discovery when most market participants become passive price takers, as the Grossman-Stiglitz paradox stipulates. There must be some profits associated with discovering the “true” price of an asset, because if there weren’t, no one would expend resources to do it.

Another way finance people say this is that “spreads are tight,” meaning that the bid-ask spread, the distance between the highest price a buyer is willing to pay and the lowest price at which a seller is willing to sell, is relatively small. Smaller spreads generally means that there are a lot of transactions and therefore more liquidity.

Keynes thought that the “fear of goods” was a major driver of chronic unemployment and under-investment, because skittish financiers would rather hold onto cash or cash-equivalents than actually put their money to use (and thereby expose it to illiquidity). As he wrote:

Money, as it is well known, serves two principal purposes. By acting as a money of account it facilitates exchange without its being necessary that it should ever itself come into the picture as a substantive object. In this respect it is a convenience which is devoid of significance or real influence. In the second place, it is a store of wealth. So we are told, without a smile on the face. But in the world of the classical economy, what an insane use to which to put it! For it is a recognized characteristic of money as a store of wealth that it is barren; whereas practically every other form of storing wealth yields some interest or profit. Why should anyone outside a lunatic asylum wish to use money as a store of wealth?

The most legendary private fund of all, the Medallion Fund, which was created by the late mathematician-turned-hedge fund manager Jim Simons, is famously not open to outside investors. As Matt Levine put it, why enjoy 20% of the profits when you can have 100%?